Setting the Pittsburgh to DC Fastest Known Time

By Dylan Stagner

Anyone interested in this should also read the trip reports by Chris Shue, Aeden Hale, and Kevin Beck.

Inspired by Kevin, I’ve tried to organize my this in a way that might be useful for anyone attempting something similar. If you just want to read our ride report, skip to the Execution section.

The Route

The GAPCO route is a treasured gravel trail network that runs between Pittsurgh and Washington DC. The “GAPCO” name is shorthand for its two component trails: The Great Allegheny Passage between Pittsburgh and Cumberland, Maryland, and the C&O Canal Towpath, which connects Cumberland to DC. The full length of the route is 334 glorious car-free, gavel-full miles, following two major river systems, crossing the Eastern Continental Divide, and interacting with a lot of fascinating history along the way.

Jeremy’s Strava Upload

Great Eskape president emeritus Andy Karr wrote an excellent primer on the trail, and what it means to people like me who’ve fallen in love with it. If you’re not familiar with the GAPCO, that’s a great place to start.

Generally, this route is done as a 4 or 5 day bikepacking trip. I’ve done it at that pace 3 times, and it’s a real treat. If you’re trying to decide between that version and the sub-24 hour approach described here, I’d recommend the former.

The Crew

Myself, your humble correspondent. A heavyset masher with a lead foot. A moderately successful cross racer, an aspiring crit specialist, and a once and future clydesdale. Known to overwrite.

Jeremy Gardner aka Jerry aka Jerbear. A casual powerhouse in single speed cross races and most any other endurance event he puts his mind to. Half man, half crystallized athleticism, half detailed knowledge of bird migration. Where there was one set of footprints on the beach, that’s where Jeremy was carrying you.

Planning and Motivation

Jeremy and I had been casually discussing this for a while, but I think we got more serious about it when the world shut down in 2020, and we lost all our opportunities for racing. I was aware of Chris’s ride the previous summer, and by the time we started talking about it, Aeden and Spencer had already lowered the FKT to 23:06. This felt like a beatable time for Jer and I, and we started talking about this as a record attempt.

Despite the fact that time had long since lost all meaning, we settled on October 3rd as our departure from Pittsburgh. This worked out well for both of our schedules, but we gave up some daylight and meant we were taking a bit of a chance on the weather. Fortunately, it would hold out for us.

With less than a month to go, Kevin came out of nowhere and took another 13 minutes off the record, finishing in a very impressive 22:53 solo. Again, Jeremy and I figured this was a beatable time for us, and we sketched out a rideplan around that. Among the highlights of this rideplan v1.1 was a stop at the Sheetz in Hancock, MD, at mile 206 or so. I’m a sucker for Sheetz’ brand of computer-aided fried goop, and I figured that it would be a strong motivator as night set in. We were planning around a 22:30 finish, which would have been tough, but we were very convinced that it was do-able.

And then on the Thursday before our trip, I was stalking Kevin’s ride on strava, and I saw Jeff Koontz’s post mentioning that he was giving it a shot. I creeped Jeff’s strava, and my heart sank. Jeff had crusht it, taking 1:17 off Kevin’s already impressive time.

Just like that, the time to beat was 21:36. Jeff averaged 16.8 mph while moving and stopped for around 100 minutes, both of which are extremely aggressive and exceeded our original goals. For the first time, I started to think we might not be able to bag the coveted GAPCO record and score all these priceless internet trashtalk points.

Make no mistake, we really, really wanted the record. Straightshotting this is “fun” and worth doing for its own sake, but Jeremy and I are both pretty competitive, and we basically funneled an entire year's worth of race hype in to this one big dumb ride. We both talked about only wanting to do this once.. and though it was unsaid, I think there was always an implication that if we didn't get the record on our first go, we'd probably try it again. As much fun as this was, I'm very thankful it didn't come to that.

So all our plans were out the window. We’d have to shave an hour off our 22:30 plan to beat Jeff.

Our gameplan was to go out hard and fast early, and expect to blow up a little. Chris, Kevin, and Aeden all talk about falling apart in the last 50 or 60 miles, and Jeff ran into weather and mechanicals towards the end of his ride. Point is, you can't really count on carrying your mile 0-50 speed on mile 280-335.

As in all aspects of life, the best part of cycling is spreadsheets. I worked backwards from Kevin’s and Jeff’s times and set intermittent time goals.

I’m something of a scientist myself

To break the record, we’d have to maintain an average elapsed speed of at least 15.6mph. Not hard to keep that speed up while moving, obviously, but a lot harder to maintain while refueling and resting. To beat Jeff, we decided we had to “win the stops.” Which is to say: not stop very much. But most importantly, we’d just have to keep that elapsed average speed up above 15.6. This became my guiding principle, and I’d spend the entire ride with one eye on the Elapsed Speed window on my Garmin.

Training

In his write-up, Kevin really dove into the data here, but this is probably the section about which I have the least advice. In short, I think that if you’re going to ride a lot in a short period of time, you should prepare for that by trying to ride a lot over a long period of time.

Fortunately, I was able to leverage a bit of third party insight. In anticipation of a racing season that never happened, I had started working with a cycling coach, Billy Edwards, for the first time in 2020. I’d hoped to use his expertise to improve my sprinting ability and get a few upgrade points in the crits, but--as with so many of the best laid plans of 2020--that wasn’t in the cards. We shifted gears mid-summer and started training with this ride in mind.

To that end, I put in a fair amount of threshold and subthreshold work, and I completely abandoned any attempt to cultivate snappy sprinter speed. I also dragged a lot of friends on longer than practical rides, with 4 120 mile+ days in August and September. Shout-out to Brian Crowe, Kevin Sundeen, Alex Hinton, and David Stauffer for humoring me over those long, hot, late summer days.

For his part, Jeremy put in a thousand mile month in the lead-up to our attempt. Seems like it worked for him.

Gear

We both rode our regular cross bikes, which you can read about here on greateskape.com. Of course, Jeremy’s rig is singlespeed, because Jeremy is... different. I would be very hesitant to take on something like this with anyone else who wasn't riding geared, but it didn't really concern me in this case, because Jeremy is... different.

We both used Conti Terra Speed tires, which are highly rated by bike tire rolling resistance dot com and more importantly, Andy Karr.

An obvious concern for any overnight biking adventure is lighting. I’ve long-since adopted rechargeable lights for my commuting needs, but these are mainly for be-seen purposes riding in traffic. Taking on the Canal at night necessitates a brighter, longer lasting solution. In his write-up, Kevin noted that he wished he’d had more powerful lights, and he reported that his lack of visibility really affected his morale, which I could totally see happening to me as well. I let my tendency to overcompensate and over-prepare guide me, and I landed on a Light & Motion vis Adventure setup with external 6 cell Li-ion battery, which boasts an impressive 800 lumens on the highest setting. Combined with Jeremy’s 400 lumen Fenix BC21R V2 setup, we were able to cut a nuclear bright path through the dark.

L&M Vis Adventure with battery

My only complaint with the L&M rig was the handlebar attachment, or lack thereof. I ended up having to use an L&M Gopro adapter, and a Gopro handlebar mount, which gave the light a sort of periscope sensibility. I also double-wrapped my bars to give my hands a break, and strapped on a small handlebar feedbag to hold the external battery and give me some more cargo space. Combined with my Garmin 800 and supplemental battery, my cockpit was busy busy.

heard you like bike gizmos so we put a gizmo on your gizmo

Because we cut out the Sheetz refuel, we needed to absolutely load ourselves down with calories. I carried around 20 bars, 20 gels, 8 Tailwind high calorie drink mixes, 4 Scratch drink mixes, and a peanut butter, honey, and banana tortilla wrap. About a third of my bars, half of my drink powders, and all of my gels had caffeine. I had two bottles on my frame, and a 1L camelbak with some pockets for extra snacks. Jermy had three bottles, and a similar amount of food, with a plan to eat 250 calories an hour.

In the dark, all Cliff bars taste the same.

Execution

If you’re reading this in the distant future, years from AD 2020, you may have forgotten about .. what happened. I mean, Jeez, I hope you have forgotten it. I hope it was temporary. But the tl;dr is that the human body is fragile and susceptible to pathogens, of which we had one in this particular year. And so we all stayed indoors for a bit, but then after a while we didn’t stay indoors as much. It wasn’t ever clear to me when and why we crossed that line or why, or if we really should have done so, but I digress. In any case, it sorta felt okay for Jeremy and I to share a hotel in Pittsburgh on October 2nd, 2020. Reasonable people may disagree with this decision, and I won’t fault them for it. But oh man, what a hotel room we got!

Yinz can see your house from here.

Turns out there is an advantage to traveling when traveling is difficult and dangerous. A ~20th floor view of Point State Park is something I’m glad I got to experience.

We'd loaded up on bagels from Dunkin Donuts the night before, in anticipation of not finding an open breakfast spot at 6:30am in These Unprecedented Times. Fortunately, we discovered an open Starbucks, allowing us the luxury of a two course breakfast.

Elevator lobby at the PGH Wyndham Grand, featuring infinitely recursive Great Eskape

I crushed a bagel, a donut, a banana, a can of beet juice, a breakfast sammy, and an espresso from the sbux. We made a perfect GrEaT EsKapE tImE 7:00AM departure, and were wheels down at 7:20, following a photo sesh at Point State Park.

GAP Mile 0. I mean, gorsh, Pittsburgh.

One downside to doing it this late in the year: October mornings in PGH are not warm. My Garmin recorded a low of 37 on that end. I started out wearing literally all my available clothes: jersey, bibs, vest, arm warmers, leg warmers, mid weight gloves, hat, and neck gator.

Smiles and smizes before we set off. Note Jer's knog / zip tie collabo headlight

This was my fourth time doing the GAPCO trip, but my first time to leave Pittsburgh on the correct side of the river. Turns out, you’re supposed to stay north of the Monongahela until you reach the delightfully named Hot Metal Bridge, which, on that day, wasn't.

The paths were pretty empty at that hour and temperature, and we didn’t see many people. The fog was thick and cold coming off the Monongahela, and my hands and feet were soaked and cold for an hour or so, but the sun peeked through early and warmed us up by around 9.

30 miles in, enjoying crunchy leafs season

Traffic was light on the trail, but we did see a few other cyclists heading out of Pittsburgh in the early morning. We were making great time, and our elapsed average speed was holding around 18 mph.

Things were going a little too well until about mile 40, when Jer dropped back a bit and then called out “I need to stop.” He was looking at his rear wheel when I circled back, and I assumed that he had a brake rub or something similar. “I think I heard a puncture,” he said, and my stomach dropped. One thing we really couldn’t afford was to lose time to a flat. Sure enough, we found a tiny hole gurgling tire milk sealant. Luckily, the tire seemed to seal up, and it didn’t lose too much pressure. I spent the rest of the ride silently worrying about it, but I didn’t want to jinx anything by talking about it. Jeremy just #seemsfined his tire pressure for the next 290 miles, like you do.

Recovered from that scare, we rolled into our first planned stop in Connellsville at mile 59. There’s a small camping area with nice Adirondack shelters and a water fountain right off the trail. We refilled bottles, and I slammed my peanut butter tortilla (the only “real” food I ate all day). Jer pulled out his last Dunkin bagel and said “Well this isn’t going to get any better” before wolfing it down.

We were back on the trail in 10 minutes. As we hit the stop, we were comfortably above our necessary pace, still clocking an elapsed speed of 17.9 mph. By the time we left, our short break had reduced that to 17.4mph. The cost of downtime made real!

The stretch from Connellsville to Ohiopyle is some of the prettiest riding on the whole route. The sun was shining and we made great time. There was a bit of pedestrian traffic outside of Ohiopyle, but we picked our way through. A shame not to be able to enjoy the bridge over the gorge, but no time for a stop as we started the gradual climb up to the Eastern Continental Divide.

The divide climb is death by a thousand cuts. The overall grade is maybe .5% from Ohiopyle to the top, but there are a few steep pitches, and it wears you down over time. We were still trying to cook it to stay ahead of our goals, and I started to worry we were burning too many matches. More than once, we eased off the gas for a second to try to recover. In retrospect, I think we left a little time on the table here, but it’s hard not to be a bit conservative knowing that you have 250+ miles left to go.

At the top, we took a few minutes to eat and put some clothes on before the descent. We talked to some folks there about our ride. They were excited to hear of our goals, and I found their enthusiasm infectious. We pulled off feeling great about our progress.

The descent in to Cumberland

The descent from the Divide into Cumberland was a real treat. Jeremy’s single gear spun out at a little over 20 mph, so we were content to cruise it at that pace. I snapped a couple photos on the descent, not realizing they would be the last pictures I’d take for the next 9 hours.

May the wind be ever at your back and the snot be ever in your moustache

Our longest stop was at the bottom of the hill in Cumberland. There’s a nice little public square where the two trails meet, complete with bathrooms and water fountains. I updated the Great Eskape slack on our progress and pounded some bars. Jeremy swapped out for the fresh set of bibs and jersey he’d been carrying, which made me a bit jealous.

We already had a solid day’s riding behind us as we rolled out onto the C&O, just 185 miles left to go.

Although they’re both described as gravel trails, the GAP and the C&O are noticeably different in ride quality and appearance, with the C&O being by far the rougher of the two. The towpath gravel is bigger, lumpier and less refined. The biome on this side of the divide is decidedly less Appalachian and mountainous, and it really starts to hint at the mid-Atlantic swamps I call home.

Both trails are well posted with a marker every mile, but the counts run in opposite directions, with GAP mile 0 in Pittsburgh and C&O mile 0 in DC. The full GAPCO means counting up to 150 and down from 185. It was motivating to watch the posted numbers grow smaller as we whittled down the remaining distance.

Logistically, the biggest difference between the GAP and the C&O is the opportunities for water resupply. The GAP is littered with trail towns and public municipal parks, many of which have regular water fountains and spigots set up for thirsty bikepackers. On the C&O, the Park Service has installed hand-operated pumping stations. These feel a bit antiquated and require a nonzero amount of effort to draw somewhat metallic tasting water, but their frequency along the trail makes a straightshot like this possible.

Great Eskaper Alex Beszhak demonstrates C&O water pump operation in May 2019 (Photo: Edrie Ortega)

After filling up in Cumberland, we planned to hit two pumping station top-offs on the way to DC.

We still had a couple hours of daylight to work with after Cumberland, and our spirits were probably at their highest of any point during the ride. The first thirty miles passed without incident, as we enjoyed the afternoon sun and the just-unnoticeable negative grade of the C&O.

We reached our first major landmark right at 6:00pm, as we crossed mile 175 and turned a bend to see the legendary Pawpaw Tunnel ahead of us.

Entrance to the Pawpaw Tunnel (from Wikipedia)

As of this writing, I’ve crossed through the Pawpaw Tunnel five times and hiked over it once, but it never gets any less spooky. Built to avoid a series of bends in the river, the tunnel is cut three quarters of a mile under the rolling hills of Western Maryland. As with the rest of the C&O, it contains both a canal and the accompanying towpath, but here, in darkness. On approach, it offers a well framed void, with no apparent end. From inside, the dark and the curve of the brick walls inspire claustrophobia, while the drop off from the towpath to the canal at least suggests a fear of heights. Plus, you gotta figure the bottom is just full of like snakes and spiders and full-blown cryptids. And the dark, it’s very dark inside

View from inside the Pawpaw, May 2020 (Photo: Andy Karr)

My general approach is usually to roll up slowly and walk my bike through the tunnel. I thought I had communicated this to Jeremy, but he took the initiative and just pedaled through it like an absolute boss, giving me no choice but to follow. And as it turns out, you can 100% just roll that sucker, if you can avoid thinking about.. well, everything. It probably saved us 15 minutes to take his approach instead of my overly cautious version, and we emerged to dusk on the other side.

We stopped for a moment on the DC side of the tunnel, and I think that marked the end of our lightheadedness, and the beginning of The Work We Had to Do. Our Elapsed MPH was still in great shape at 16.6, but the sun was setting, and we still had to put in 155 miles to Georgetown. We set off again after a minute, and I tried to steel myself for the difficulty and weirdness to come.

I wish I had some clear memories of the next few hours, but the truth is that they were a bit of a blur. Nightfall passed without incident, and we both switched on our headlights. Between my L&M rig, and Jer’s Fenix and zipknog special, we blazed a bright trail, and it must’ve kept us safe, because neither of us remember any incidents caused by our lack of sight. At some point in this stretch, we must’ve stopped to pump water, but I couldn’t tell you where, or how it went.

I do recall the Big Slackwater in the dark. This might be my second favorite feature on the C&O, following only the above mentioned tunnel. At the Big Slackwater, which is roughly 90 miles from DC, the Potomac grows wide, and the towpath snakes alongside it on a concrete boardwalk. Mostly, this feels pretty safe, but the delta between the boardwalk and the river below is at least ten feet, and some of the turns come up on you pretty fast and gravelly, especially in the dark. Four months after our FKT ride, Jeremy and I crossed the Slackwater again in the daylight. It’s always a stunner, especially compared to the green tunnel sensation of the Towpath.

Jeremy and the Big Slackwater, January 2021

We made our last "real" stop in Harper's Ferry, getting there just after midnight, 16:40 and 271 miles on the ride clock.

Neither of us could remember seeing a water pump there in the past, but we were hoping to be able to fill up again. Spoiler alert: there are no pumps at Harper's Ferry. It was cold and windy, and a train rolled in just as we did. As it howled along the tracks overhead, I crammed another bar and sent the Great Eskape slack a very cryptic message: "Harper's Ferry. Pushing. Please bring us warm clothes?" This made total sense to me at the time, but in retrospect it does not read as a complete thought. Thankfully, Kelley MacEwen did the math and worked out that we'd be ahead of our estimated 4:30am arrival if all went well. What a hero.

By this point, the fatigue and the cold had definitely caught up with us, and we were full on loopy. We struggled with the very simple tasks we had set up for ourselves, such as eating and standing up. Jeremy got some food (or something) out of his saddlebag and started adjusting something around his handlebars (I think). In the interest of saving us a few seconds, I reached over to close his bag, silently congratulating myself for being such a good friend and teammate. However, this being a new buckle that I had never encountered before, I was completely unable to figure out how it worked. I found myself totally defeated by the idea of a new luggage closure. I laughed and told him my hands were “too dumb” to work it out. Thankfully, he remembered how, and we were able to pack everything up and keep moving.

Leaving Harper's, it took us a while to warm back up, but I started to let myself be confident that we could break the record. Our elapsed average was holding on to 16.1, and we had just under 5 hours to cover the last 60 miles. We also knew we needed at least one more water re-fill before the end. Frustratingly, we passed 3 more pumps with the handles removed before we finally found one that was operational, around mile marker 40. There were several tents nearby, and I know we weren't able to be quiet while we clanged the pump around. Apologies if you were camping on the canal that night and got woken up!

The closer we got to DC, the more familiar the towpath was. We got a big jolt of adrenaline passing Great Falls. Like everywhere else on the canal, it's spooky and empty at 3am in the cold, but I was starting to feel like I was home.

Our speed was still good, and we started talking about breaking 21 hours, which we hadn't really given much thought to previously. Jeremy suggested laying down some speed starting in Fletcher's Cove (mile 3ish). I agreed, although we both laughed because "some speed" at that point meant maybe 18 mph. We ended up averaging 17.7 mph from Fletcher's to Key Bridge, and it felt like a huge effort.

Incredibly, we had failed to correctly sort out the exact path to mile 0 before the ride. I wanted to make sure that we did the exact same thing Kevin and Jeff did, so I tried to steer us to the end of the towpath, rather than cutting under the Whitehurst Freeway like I usually do coming off the C&O. Of course, I guessed the wrong footbridge over the canal, and we had to backtrack slightly. On the second try, we got it right, and worked our way over to mile 0. As we pulled into the boathouse parking lot, we could hear cowbells and cheering from our teammates Kelly Roberson and Kelley MacEwan. Another teammate, Alex Hinton, showed up just a moment later (when we'd originally planned to finish). They had jackets and blankets and donuts, and best of all, friendly, congratulatory faces.

Kelly, Kelley, and Alex. I hope you have such great friends and I hope you take better pictures of them.

333.53 in 20:52:58 according to Strava.. but we've been, uh, rounding that down to 20:52.

334 miles later, still smiling, still smizing (Photo: Kelley MacEwen)

Keeping ahead of our elapsed average speed goals worked well for us, as we limited our stoppage to just 77 minutes over the whole route. Our moving speed was a pedestrian 17 mph, but relentless forward motion carried the day for us, and our elapsed speed was 16 mph flat.

Aftermath

It should come as no surprise that this is not a kind, loving thing to do to your one human body.

Kelly was nice enough to drive me the 3 miles home from the trailhead to my house, and even nicer to lug my bicycle up to my 2nd floor apartment. (Without her help, I probably just would’ve locked it to a tree and hoped for the best). I took a longg shower and laid down for what should have been the most restful sleep of my life at about 6:30 AM … and by shortly after 7, I was wide awake, the combination of the previous night’s caffeine, adrenaline, and actual godshonest daylight too much for my body to handle.

Jeremy was saved by the graciousness of Kelley, who gave him a spot in her guest room for a few hours and fed him a well deserved non-gel breakfast. Later that morning she dropped him off at Union Station for the final leg of his return trip to Baltimore.

I spent that Sunday in a fugue state, periodically responding to congratulations from my bicycling friends and wellness checks from concerned family members, and attempting to navigate food delivery apps. I’m pretty sure I napped a lot and ate a lot and moved very little, which was definitely called for.

But if a robot didn’t tell you as much, how would you know that you had actually worked hard? How would you know whether or not you had had any fun and of what type? These are the questions that plagued the endurance cyclists of days gone by. Fortunately, we no longer have to wonder; our world is full of robots with opinions. For starters, when you upload a GPS file with heart rate and power data to the Strava dot com bicycling website, a robot will tell you how your effort compares to your recent rides.

A higher than average effort for me. Strava robot says so

Of course, if you don’t collect heart rate and power data, you can provide the information yourself, by means of a “Perceived Exertion” manual input.

Jeremy's helpful analog feedback on his Strava ride

Personally, I’m not satisfied by strava’s algorithms, and I track all my fitness and recovery information via a Whoop band, which is a machine for quantifying the tiredness of gullible nerds with disposable income. Every day, whoop assigns a recovery percentage based on your sleep quality, heart rate, and prior day’s effort. I have almost two years worth of Whoop tracking and it’s always given me a recovery score. Even on nights with short, restless, boozy sleep, Whoop will report a 5 or 10% recovery.

This ride was the first time that Whoop tapped out and didn’t even try to assign me a recovery score. I guess that’s a useful datapoint in itself.

Divide by zero error. Whoop robot says so

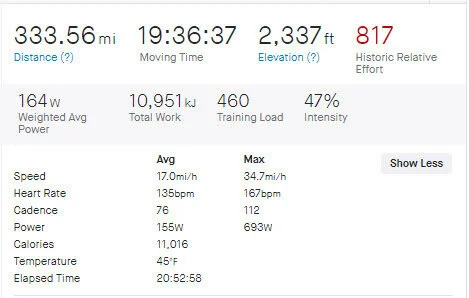

A few other notable metrics, from strava:

Disregard the cadence figure, which can't be right. Even I don't mash that hard.

All of which is to say that I was pretty heckin sore and tired for a few days. I treated myself to a week of complete rest and a lot of stretching, but I was back on my bike for an easy spin the following Sunday. Seems fine.

Concluding thoughts

This was an incredible day, and I’m proud of the fact that we got the FKT. Four months later, I still return to the pictures and thoughts of that day, and I hope to carry those feelings with me for a long time. In such a weird, difficult time, I’m truly blessed to have had such an experience, and I’m thankful that it went so well. It’s worth noting that we caught a lot of luck along the way. The weather, while chilly, was dry and calm, and other than Jeremy’s momentary tire hiccup, we didn’t have any mechanical issues. Our bodies held up and our food held out, and perhaps most improbably, our morale stayed high. Everything had to go just right for us, and it did.

There’s still a lot of meat on that FKT bone, though, and I fully expect our time to be handily beaten before too long. When that happens, I’ll gladly cede the crown; I have little interest in mounting a title defense for this route. If I ride the GAPCO again, it’ll be party pace, and I look forward to having some real Type I Fun.